I bumped into this headline while searching for something else, and I decided I had to take a look at the Elms Hotel. It hadn’t hit my consciousness when I was researching Grand Hotels for my talk for the Historical Society https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PkPBikpIv2I

It flourished between the 1893 Fair and the second outburst of hotels after World War I. It stood on the northeast corner of 53rd Street and Cornell Avenue when there was little between it and East End Park. As a result, it captured the population who wanted the fast connection downtown on the Illinois Central, residential hotel luxury near a park, and the cooling breezes of the lake before air conditioning. The IC, just a short block to the west, ran over a hundred trains a day and the trip took just 9 minutes. The article was an interview with the manager of the hotel from 1905 to 1925. He remembered that actors performing in the Loop were an on-going part of their clientele, particularly the stars of Broadway touring the country. I had to check Wikipedia for most of the people on his list, though I knew a few.

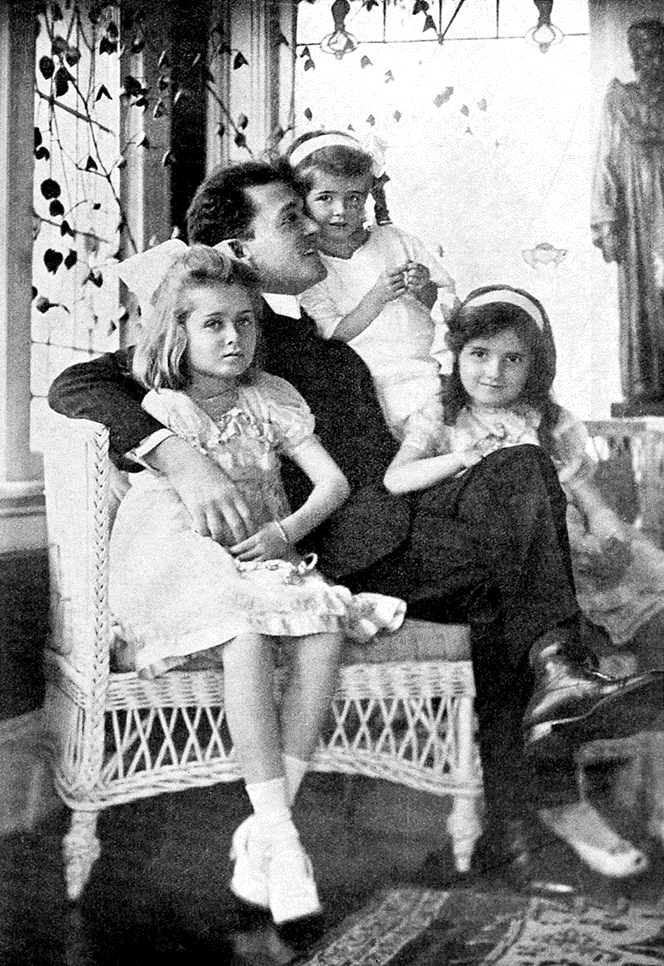

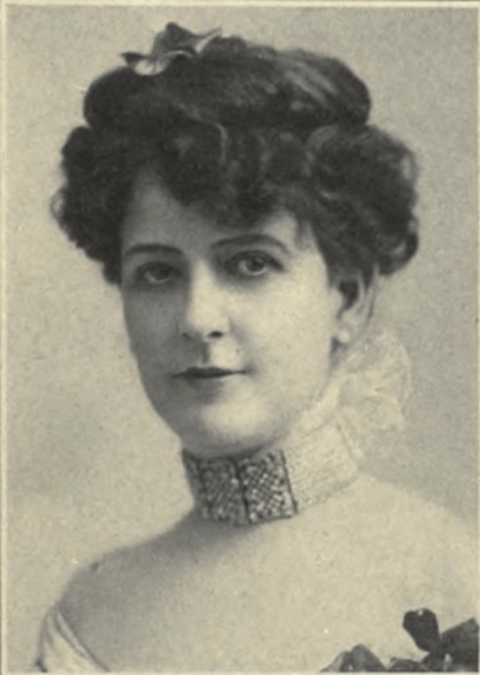

He particularly remembered Richard Bennett. In the period he might have stayed at the Elms, he had a lot of roles, including the lead in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman. He starred opposite Maude Adams in James M. Barrie’s What Every Woman Knows. It may have been his tour with the play Damaged Goods (1914) that the manager of the Elms remembered. His co-star was his wife, Adrienne Morrison. The Elms’ manager particularly recalled Bennett’s daughters, future stars of the silver screen, who stayed at the hotel when they were girls. These were Constance Bennett, Joan Bennett, and Barbara Bennett. Constance and Joan had, of course, long careers in still famous movies. Barbara, however, led a troubled life. Richard Bennett made the transition into silent films and later was a character actor in the talkies.

Other people who stayed at the Elms Hotel were Douglas Fairbanks, Sr., Frank Craven, May Robeson, C. Aubrey Smith, and Victor Moore. Fairbanks, of course, was the great athletic action hero of the silent screen. Victor Moore had a long career as the star of musicals in this era and later had a long career in Hollywood as a comic foil. Frank Craven was a busy Broadway star who later acted in the first run of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. May Robson was an Australian and a Broadway star, who was in many shows of the era. In her 70’s she had a career in Hollywood as a character actor.

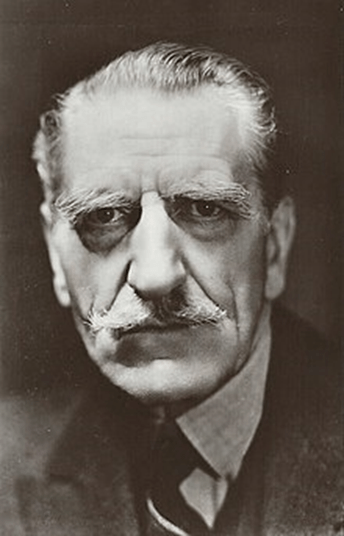

C. Aubrey Smith, who was British, was probably touring in The Prisoner of Zenda, but he made his later career in Hollywood playing stuffy aristocrats in movies like Little Lord Fauntleroy. He played Maureen O’Sullivan’s father in the Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan. His face is probably familiar if you like old movies.

The Elms seemed early on to also cater to single women who had better things to do than cook and clean. Some of the lost signatures belonged to Edna Ferber and Clara Louise Burnham, Hyde Park’s novelists. Perhaps it appealed to women living alone because the Elms Hotel was under the wing of Mrs. Anna E. Wilson.

According to the 1906 Tribune, the Elms was her creation. She chose the “soft light and silken curtain.” Anna had run a boarding house, having apparently left her husband, bringing her two children to Chicago. She invested in real estate but later lost it all. She managed to pull herself back from disaster by running a hotel during the boom of the fair, enabling her to invest in the Elms.

In its first 25 years, it featured often in the Tribune society pages, listing the comings and goings of debutantes, brides, newlyweds, single gentlemen, dentists, lawyers, and widows. They held receptions, advertised for watches lost on the train, and occasionally traveled abroad. Like all the residential hotels, the Elms provided maid service, a restaurant for all your meals, and public rooms to receive guests. It had overnight rooms, long-term single rooms, and two- or three-room suites.

Nearly every ad mentioned that it was “Absolutely Fireproof.” The Elms hosted political meetings, businessmen’s lunches, fundraisers, and debutante balls. After World War I, it was dwarfed by the new hotels one block over. The Cooper-Carleton (now the Del Prado), the Sisson (now Hampton House), and East End Park Hotels towered over the six-story Elms. There almost was another tower right across the street. In 1925, a 16-story hotel was planned for the southwest corner of Cornell and 53rd, designed by Rapp and Rapp. It would have had a large theater and shops along 53rd Street. The Elms changed owners in 1924, which was when a massive remodel happened and the hotel registry was thrown out.

During World War II, the women of the local Women’s Defense Corps of America cooked dinners of roast beef and baked ham for local service men and women, particularly those recovering in the Chicago Beach Hotel, which had become a military hospital. Each weekend about 200 pounds of roast beef, 120 pounds of baked ham, 300 pounds of potatoes, 100 pies and cakes with vegetables, gelatin molds, coffee and soft drinks were served to 800 to 1100 service men and women. Entertainers from the Loop theaters and clubs would return to the Elms to put on volunteer shows for the troops. And the hotel offered free long-distance telephone calls for the men to call home, at a time when long-distance was very expensive.

One of the bits of Hyde Park history that I haven’t quite got a handle on is the presence of the mob in Hyde Park. I’ve only caught glimpses. In 1942 there was a grand opening of a casino in the “usually sedate Elms Hotel” as the Tribune pointed out, just around the corner from the Hyde Park Police Station. The police arrested 45 people among the roulette wheels and craps tables. The hotel manager “knew nothing about it.” In 1949, the police raided again. This time it was a private club inside the hotel. But the police didn’t have a warrant so the men had to be freed. One of the names was Nick Gentile, a name that shows up in the 1920s for auto theft. Much later a Nick Gentile shows up as a “liquor dealer” connected to the syndicate’s control of vending machines. That Nick Gentile’s house was bombed in 1967. If the Elms Hotel was suspected to be mob related, that might have been one of the factors that doomed it, though legend points the finger at the Del Prado and the Shoreland for mob connections as well and they survived. Perhaps it’s that the small rooms without kitchens were hard to convert into rental apartments. The goal of urban renewal was lower crime, less density, and attracting long-term middle-class residents. The FHA was pushing all of the residential hotels to convert to rental apartments.

In the early 1950s, the Elms once more remodeled. A granite front at street level was added. The hotel touted its elegant seafood restaurant featuring lobster. However, in 1958, the Elms Hotel showed up in the long list of buildings slated for demolition by the Department of Urban Renewal. The owners fought the order, which may explain why it too nine years for it to be torn down. The owners got the lot rezoned for a 158 unit, 25-story building, but nothing happened. In 1979, a subsidized home for seniors was proposed. Finally in 1987, the low building that currently houses Athletico filled in the block that had sat empty for twenty years.

Thanks Trish – another interesting story about Chicago’s history!

LikeLike

Thanks, Martie!

LikeLike