I gave a talk on the time when the Hyde Park area was an entertainment destination and found more images than I could use. Links to the talk on YouTube appear at the end of this post.

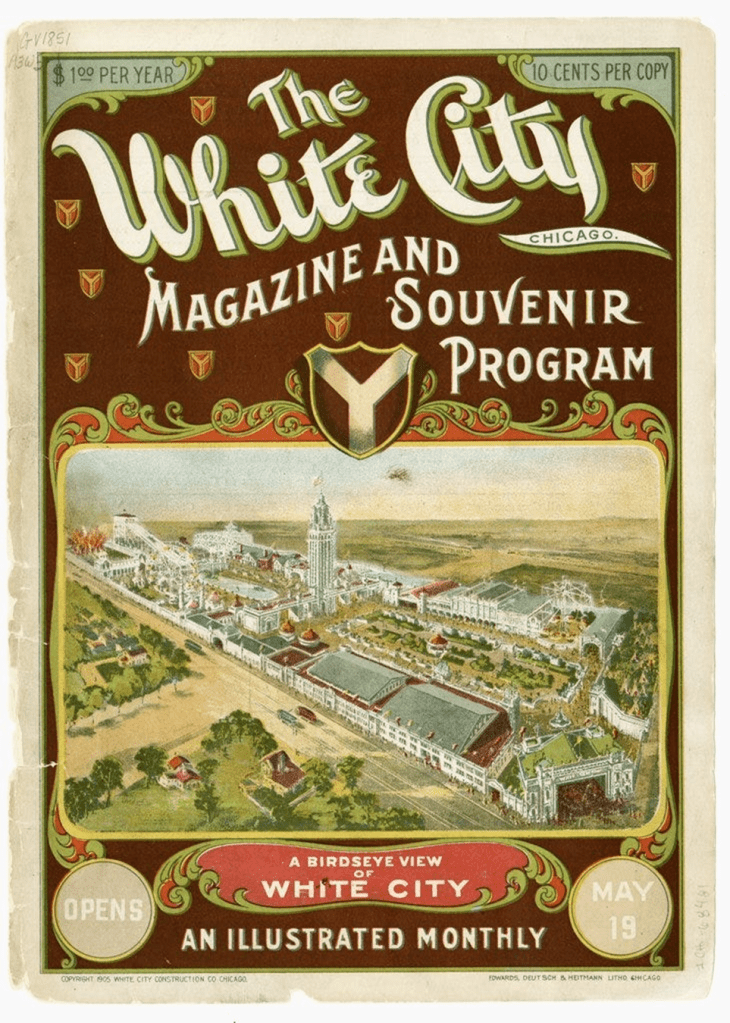

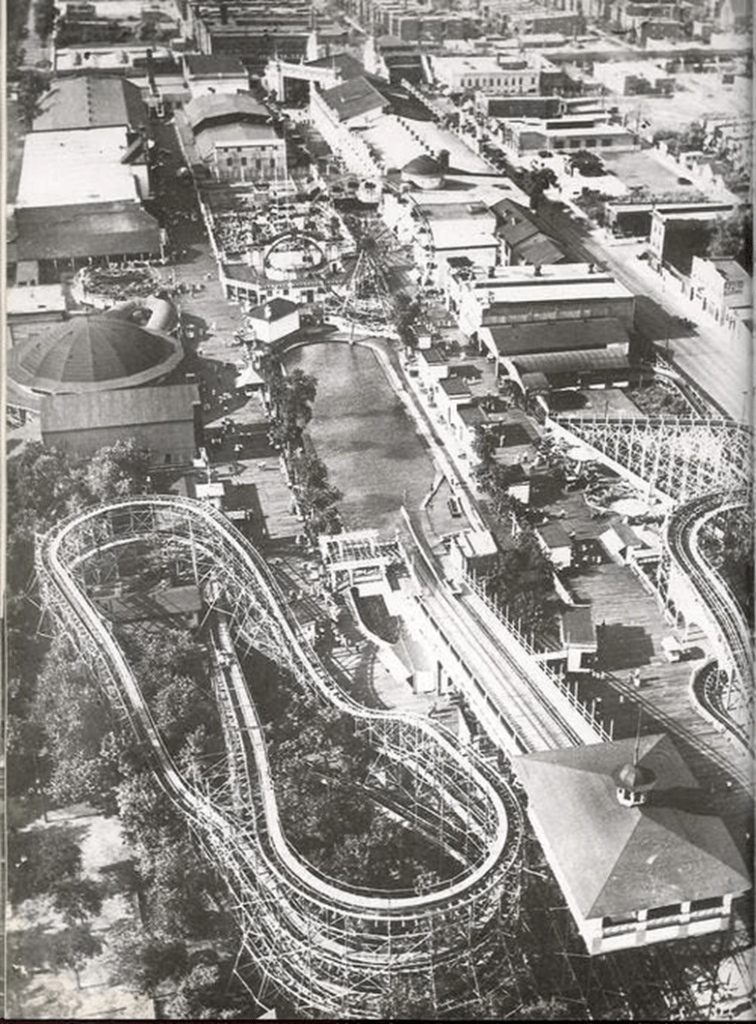

The biggest amusement park to cash in on the fame of the 1893 Fair was at 63rd and King Drive, built on a 14-acre cornfield owned by Armour of Armour meat-packing fame. It had a 1000-person ballroom, 2500-person restaurant, vaudeville stage, roller rink, and beer garden, seeking the flavor of the fair. It also took Coney Island as a model with lots of rides and funhouses. It lasted from 1904 to the mid-1930s, though the arena, theater, and roller rink lived into the 1950s (souvenir cover from Chicago History Museum archives)

The White City Amusement Park had Beaux-Art white buildings around a rectangular lagoon–a miniature 1893 Court of Honor, with a tower instead of the Administration Building. Like the Fair, the buildings were outlined in white lights. The tower was visible for 15 miles. This look–lit up tower and a central court of concessions–was a feature in over 30 imitators in the US, Britain, and Australia–all called the White City. [1905 photo (Chicago History Museum archive)]

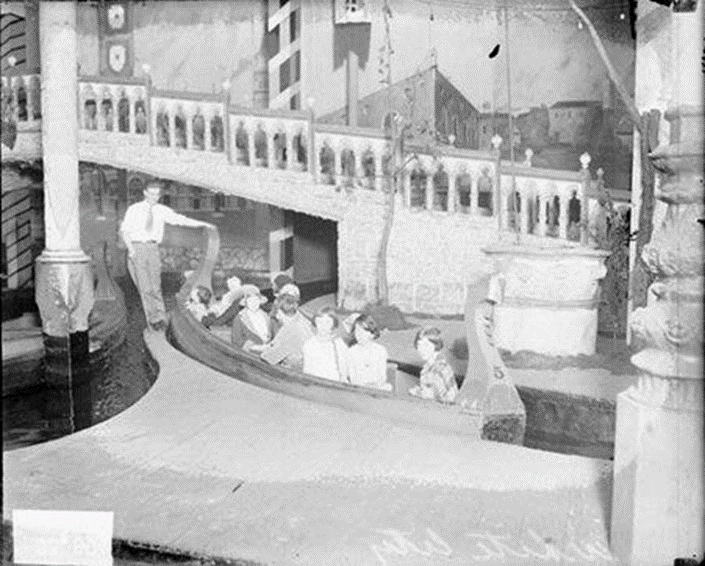

Like 1893, there were gondolas, but inside a Beautiful Venice experience, a separate concession. [1920s photo (Chicago History Museum)]

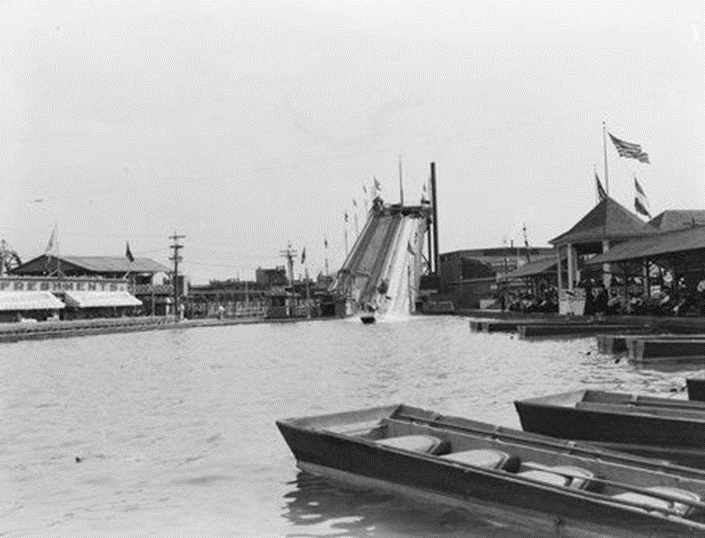

Unlike 1893, the main lagoon of the White City Amusement Park was not tranquil. A water chute sent boats plummeting into it with a terrific splash. [1905 (Chicago History Museum)]

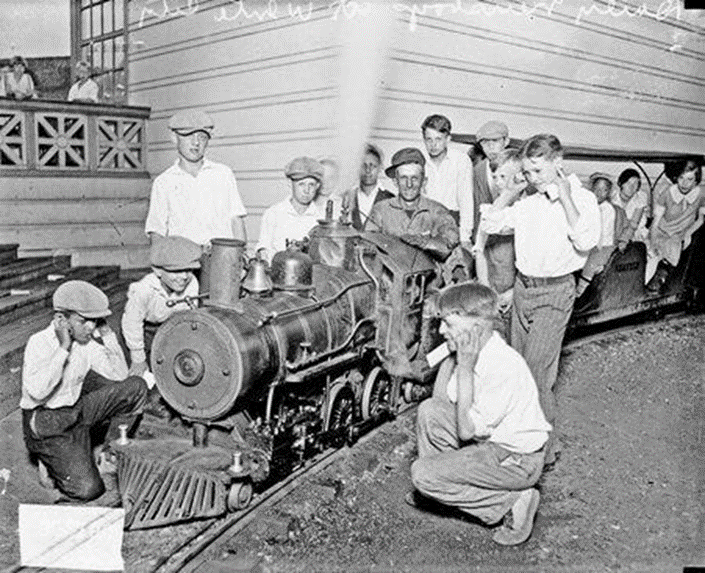

Most rides were separate concessions with a separate fee. The newsboys that sold the Daily News had a day at the park in 1928. Some of the photos are stiff and posed but they had a good time posing for this one on the carousel. [Chicago History Museum]

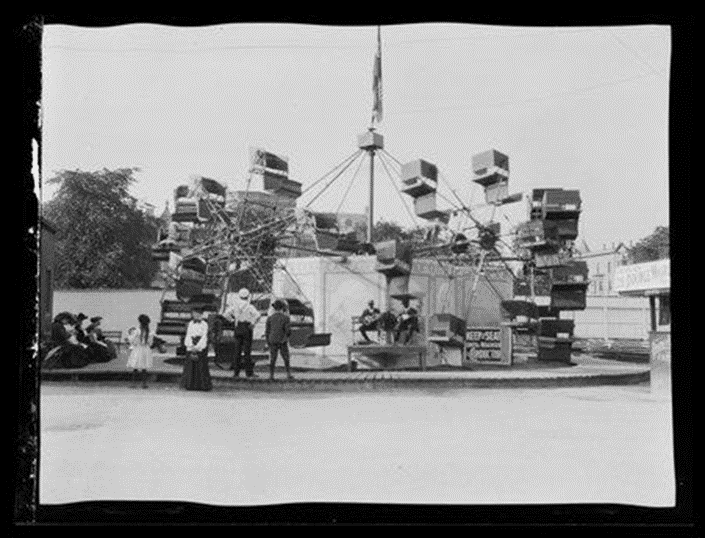

Early rides tended to be relatively sedate like the Double Whirl ride, which combined the pleasures of the Ferris Wheel and a Carousel and slowly rotated horizontally in a circle as each of six mini-wheels slowly revolved vertically.

The Racing Coaster was relatively fast and genuinely dangerous. Cars collided in 1906 and six girls were hurt. One died.

The White City Amusement Park has three footnotes in aviation history. Augustus Roy Knabenshue brought his airship (in this photo) to the White City in 1914. He’d run a passenger service in California for two years but had run out of people interested in paying $25 a ride. He carried people on a half hour trip over the Loop, along the Lakeshore. His first trip included a movie cameraman. The film was rediscovered in the National Archives 2017. This airship didn’t operate long. During WWI, both Goodyear and Goodrich used the empty hanger to build airships for the U.S. Navy. After the war, Goodyear operated passenger service from to Grant Park and back. In 1919, the dirigible engine had an oil leak, it caught fire, and the burning wreckage crashed into a Loop office building. Ten office workers died, some burned beyond identification. Two passengers died as their parachutes caught fire and collapsed. Wingfoot Air Express crash – Wikipedia Here’s a film of its trip around the city.

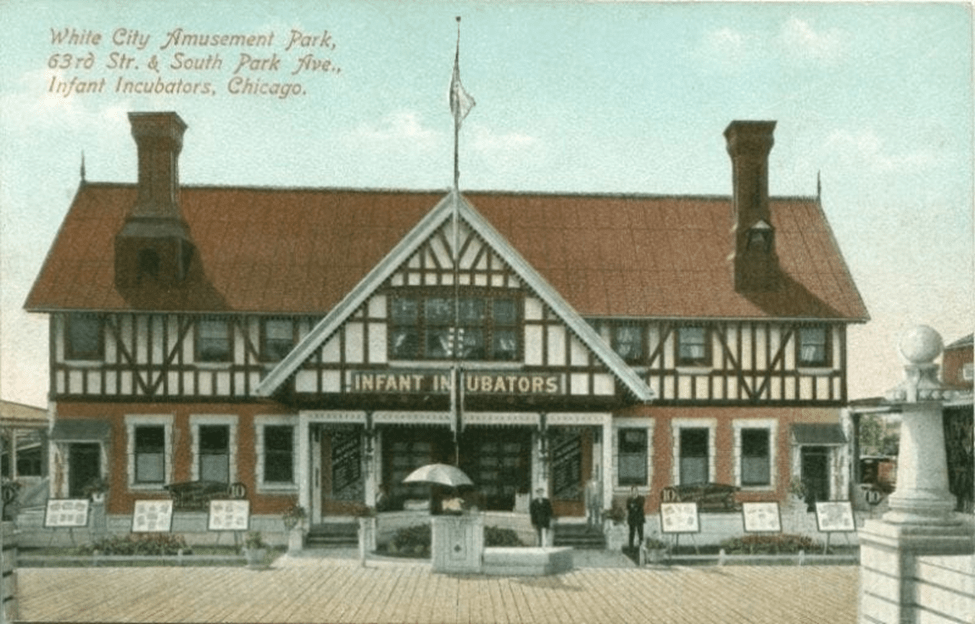

One of the concessions was the Infant Incubators. The medical establishment rejected the idea that premature infants could be saved, so Martin Couney set up an exhibit at Coney Island to prove it worked, the doctors, nurses, and incubators financed by the admission tickets of a gawking crowd. He expanded to other amusement parks, saving lives. The Tribune organized annual fundraisers at the White City Amusement Park to buy incubators for any Chicago hospitals that would accept them. Read more: (thevintagenews.com)

The Fire Show was a “mammoth spectacle of burning buildings.” It had a grandstand that seated 1500, who watched an urban scene complete with a passing streetcar and delivery wagons and 250 actors and technicians. Actors put on a street scene until someone shouted “Fire.” Buildings were “set aflame,” and screaming actors jumped from windows to life nets below as firemen doused the burning buildings. This concession was a bad omen–the amusement park had fires in 1911, 1925, and 1927. The 1927 fire destroyed the iconic tower and most of the park. The concessions didn’t survive for long afterwards. Photo Credit: chuckmanchicagonostalgia.files.wordpress.com

For much of the park’s existence, Black patrons attended though they felt less than welcome. Early on some concessions relied on racial stereotypes–including Chinese fire eaters and “wild Indians” in the Wild West Show. In 1911, the Chicago Defender complained that Black audience members were offended by a particularly bad concession. In the 1930s, a letter to the editor complains that some of the White City rides were starting to favor white children with more free tickets than went to Black children. This photo dates from the 1920s when the Daily News hosted its newsboys in the park for the day. The photo shows that some of the newsboys are Black. (Chicago History Museum archives)

By the early 1940s, the ballroom hosted legendary Black musicians who advertised in the Defender to a Black audience as well as in the Tribune. In 1942, the National Newspaper Publishers Association (an organization of Black newspapers) hosted a fundraising performance by Duke Ellington in the arena. During the 1940s, the International Sweethearts of Rhythm were a regular band in the ballroom.

The reputation for segregation comes from the White City Roller Rink in the 1940s, when racial tensions were high. The roller rink declared it was a membership club and only members were allowed in—and it was clear that only whites were accepted as members. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE, newly organized by James Farmer at the University of Chicago) tested its nonviolent tactics on the roller rink in 1942. They picketed and took the rink to court. Soon, the old White City acreage became the Parkway Gardens, a Black-owned housing cooperative. The rink changed its name to the Park City and went out of business by 1958. (Chicago History Museum archives)

Here’s my talk that covers the evolution from the 1893 World’s Fair through the big entertainment spots.