A Tale of Two Hyde Park High School Athletes Part I

This is the story of two Hyde Park High School athletes—and the road not taken. The story got a little long, so I’m sending them as separate emails.

In 1890, William Rainey Harper, the university’s first president, had the job of creating a major institution from scratch. Football was already associated with top universities. If Chicago had football, it would announce that his new university was one of them. Football would also solve his other problems—how to attract donors and students. A winning football team would get newspaper coverage, attract paying spectators, and convince Chicagoans—particularly wealthy Chicagoans—to identify with the school. Even before there were students, Harper convinced Amos Alonzo Stagg, a nationally famous baseball player and his former student at Yale, to come to Chicago. Football was so central to Harper’s vision that the first building for the University of Chicago was a shack to store gear for Stagg.

Stagg started a recruitment program that brought Chicago high school athletes to campus by sponsoring track meets and big games. He’d offer coaching and sell the charms of the brand-new campus. It was a success. Until 1929 and Hutchins turned away from sports and the city, the undergrads primarily came from Chicago. Thousands of fans swarmed the ever-growing stadium at 57th and Ellis.

Stagg insisted that players had to be amateurs and banned drinking, smoking, or gambling. Harper and Stagg believed team sports built moral fiber and all students had a sports requirement. The University of Chicago was the only Big Ten university that competed in every sport. Football, however, was always different. It was all about winning and the financial health of the school. In these early years, the football team lived in special housing in luxurious Hitchcock Hall, had their own dining table, and had very questionable academic records. The bells in Mitchell Tower rang a curfew just for them. They took gut courses with sympathetic professors who gave grades even when players never showed up in class. Harper thought they deserved special consideration because they literally risked life and limb for the good of the school. The original mass play killed and maimed dozens of college players before the rules changed in 1905. One classmate remembered the players in 1897 as “a gang of tough gorillas!” The first Big Ten championship came in 1899.

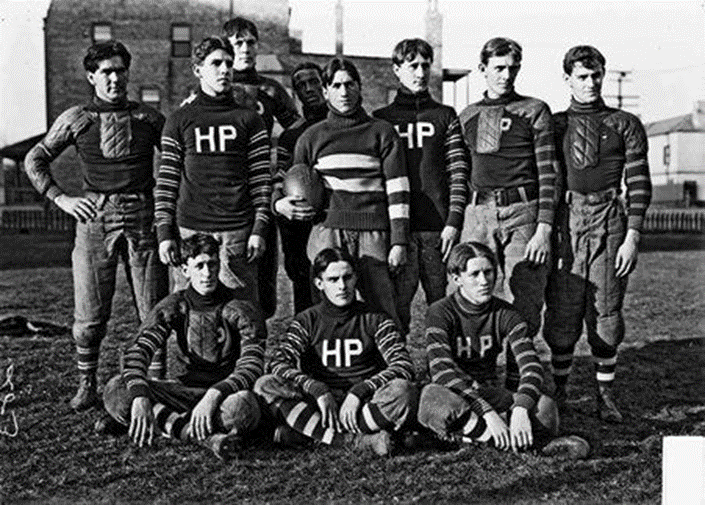

Soon after, Stagg hit the recruitment jackpot. Just a few blocks away at Hyde Park High School, located then at 56th and Kimbark, there was a player who was destined to be in all the Halls of Fame—Walter Eckersall.

He grew up in Woodlawn just south of the University of Chicago. At the track meets Stagg hosted, he set an Illinois record in the 110-yard dash that lasted 25 years. In 1901, Hyde Park High School was so good that they beat the feared U of C Maroons first string.

In 1903, he quarterbacked Hyde Park High School to an undefeated season and then led the squad to a postseason game. Brooklyn Polytechnic was the best of the East Coast and condescended to play a team from the upstart West. The game was regarded as the national high school football championship, though unofficial and was covered by newspapers across the nation. Hyde Park High School won 105–0 in the University of Chicago stadium. Legend has it that Stagg coached the team.

Alumni of Hyde Park High from even relatively recent decades can still break out into cheers of “Eckie Eckie Eckie” when Eckersall’s name is mentioned.

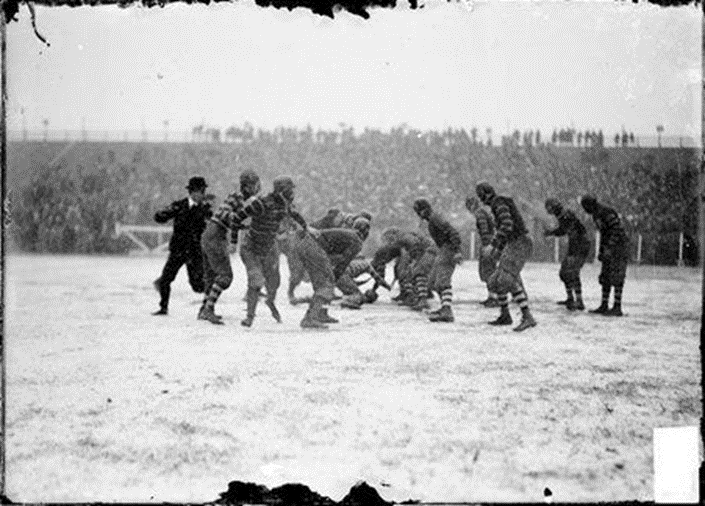

Every college wanted Eckersall. Legend has it that Stagg snatched Eckersall off the train platform to keep him from going to Michigan’s recruitment event. At the university, Eckersall led Chicago to a 25–2–1 record, outscoring their opponents 856–66. His most famous game was the Thanksgiving 1905 game against Michigan, which had gone undefeated in 56 straight games. Chicago had allowed only five points all season. Eckersall’s coffin-corner punts won the day, forcing an end-zone safety that was the only score.

Championship football brought Harper what he wanted—the affection of the city and its investments. The stadium was jammed with 27,000 fans for every game, bringing in millions. You could even buy souvenir Eckersall postcards.

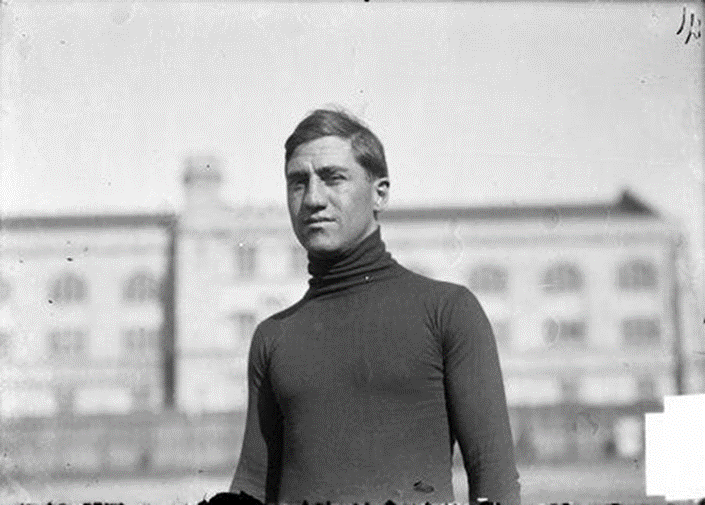

He was perfect for Stagg’s inventive genius. He was a great runner, an astounding kicker, and a formidable strategist, including on defense. At the time, players played both. He balked at only one play. Stagg proposed having the offensive line throw the 5 foot 7 inch, 136 pound Eckersall over the line of scrimmage into the end zone.

Eckersall played for three years. As long as he could win for the University, he was apparently given free rein and he didn’t use it well. The moment that his eligibility was up, he was expelled “for cause.” This was more than his woeful academic record. It was probably even more than booze and parties. Robin Lester in Stagg’s University found a letter where an old friend of Eckersall’s asked the university to reconsider, admitting that Eckersall was “a grafter as well as a monumental liar.”

He became a Chicago Tribune sportswriter and football referee. He died in 1930 when he was 43 of heart disease and cirrhosis of the liver. He’s buried in Oak Woods Cemetary. None of his personal problems or the way the university was willing to exploit him are evident in his display in the University of Chicago Athletic Hall of Fame, located in the lobby of the Ratner Center at Ellis and 55th Street.

A very different fate awaited his extremely talented Hyde Park High School teammate, Sam Ransom, who wisely chose a different path.